To understand this gallery, it is necessary to contextualize the objects and narratives it contains.

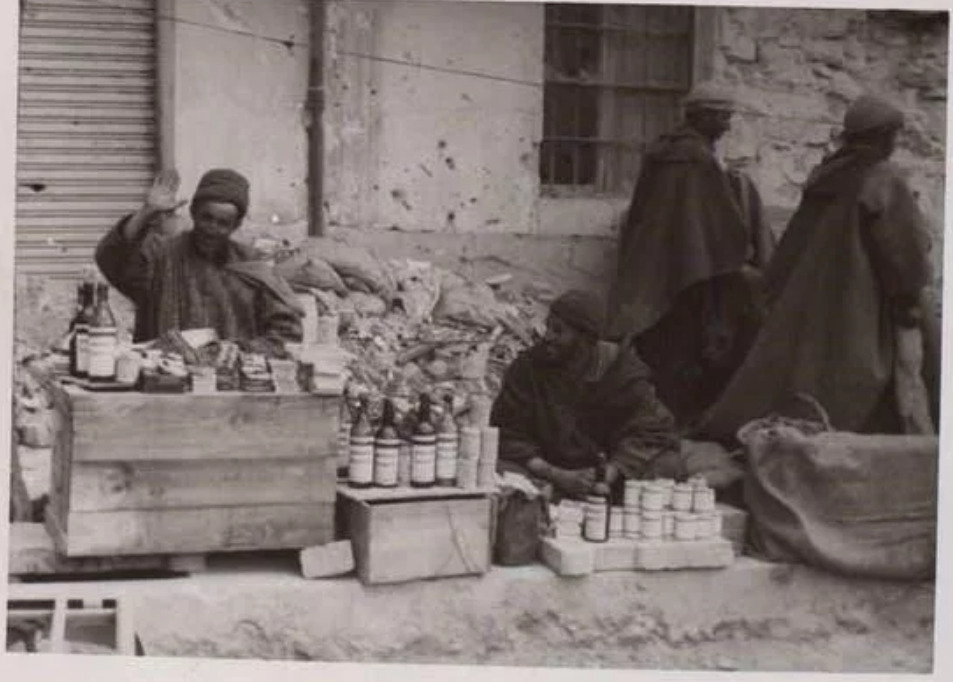

From the military coup on July 17, 1936 until the end of the Civil War on April 1, 1939 the forces of the Republic were mostly reacting to rebel initiatives. This was the case because, from the outset, the rebels had better troops, the Army of Africa. They also had international assistance from Italy and Germany that started sooner and was greater in quantity and more reliable than that the Soviet Union provided to the Republic. The rebels also had many more foreign troops. Their 180,000, comprised in order of importance, by Moroccans, Italians, Germans, and Portuguese, far outnumbered the 40,000, virtually all of them in the International Brigades, who fought for the Republic.

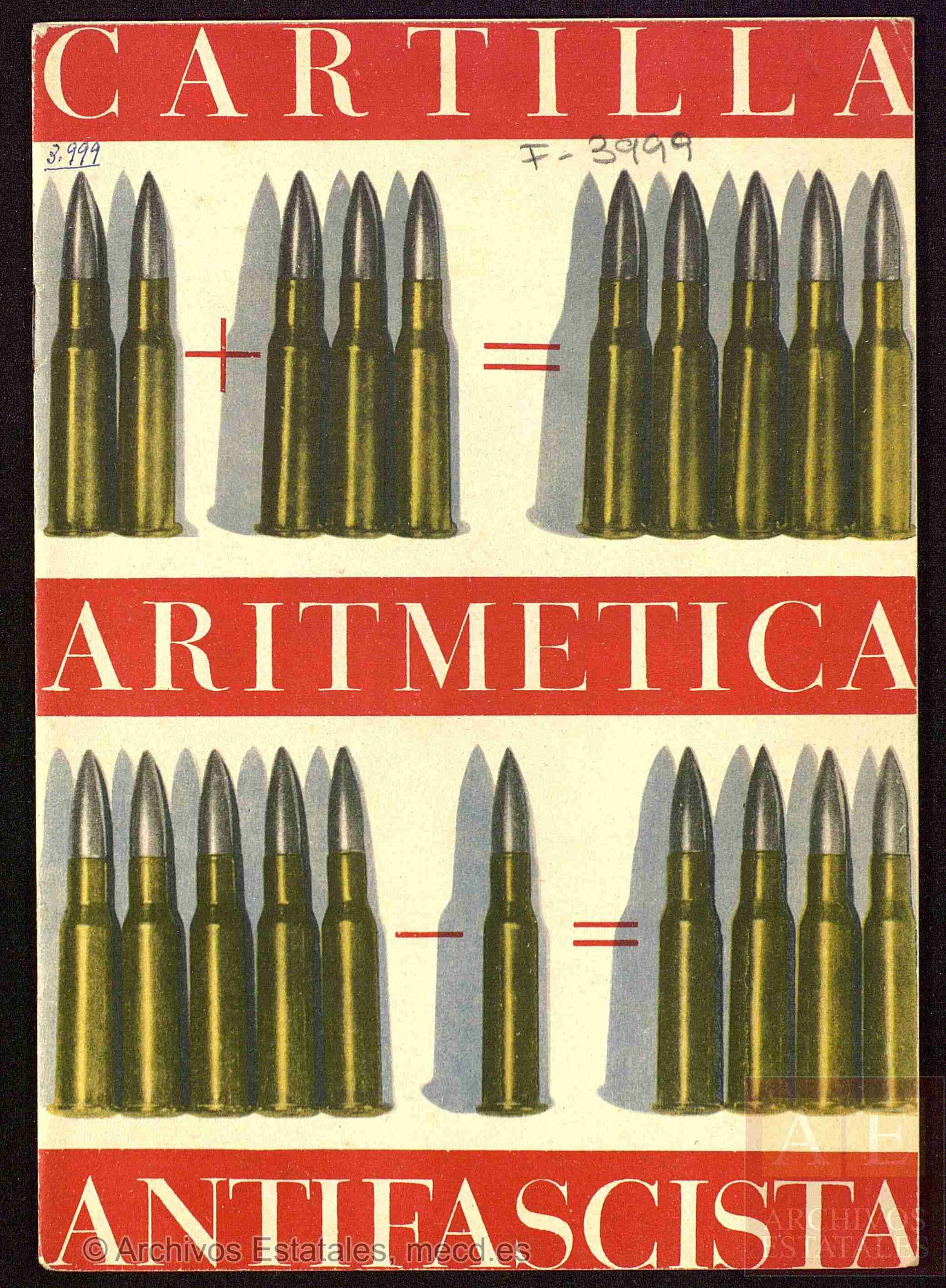

Until November 1936, there was little that the antifascist militias reinforced by the police and some military units, could do against such an enemy. Things got better after that due to the militarization of the militias and the creation of the Popular Army, and the arrival of Soviet aid and the International Brigades in September and October that culminated in the successful defence of Madrid. Despite these improvements, the Republican armies remained incapable of launching effective attacks, which meant that the strategic initiative remained with the rebels. This allowed them to conquer Málaga in February 1937 – and to lose the Battle of Guadalajara a month later.

With the sole exception of the Battle of the Ebro, from then on, the dynamic of the war remained the same. The rebels decided where to attack and the Republicans defended themselves, on occasion launching diversionary attacks elsewhere. These reactive operations, of which the northern campaign of the summer of 1937 is the best example, were costly for the Republic. It lost many of its best troops and materiel it could often not replace. What it gained in experience it lost in means. As a result, the Republic never managed to field an experienced and well-equipped army of manoeuvre that could go to critical places or launch operations that would allow it to seize the strategic initiative. When it tried, it ran up against the enemy’s superiority in men and materiel. As the conflict wore on, this disparity between the means available to the two sides only intensified.

Transcending the traditional military narrative, this gallery uses objects, memoirs and interviews to explore the daily experience of soldiers at the front, from the first days of the conflict to the Francoists’ celebration of their victory.